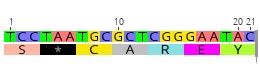

Sarah Carey

plant genomics | evolutionary genetics | sex chromosome evolution

Outreach

“Art of Biology”

In the Fall of 2015 I was the lead organizer of an art installation called “Art of Biology”. I and ten other UF Biology and Florida Museum of Natural History graduate students and researchers presented artistic images of our research subjects. This event allowed us to highlight the beauty and significance of our research to the public. At the grand opening, which attracted over 200 people from the Gainesville community, each of us stood by our art and explained the significance of our pieces and of the research it represents. Several local news outlets covered our installation including The Alligator, WUFT/WJUF, and UF News

Below are the pieces I presented and their descriptions at “Art of Biology” 2015:

Water Moss

Mosses are the tiny, green leafy things (anywhere from 0.5 to 3 centimeters in height) you often see growing on the side of trees and rocks. But if you look closely, like at this male Ceratodon purpureus plant, you can find some other brilliant colors! Also, interestingly, the leaves of this species (and most other moss species) are a single cell layer thick. As a researcher, I like working with moss because it grows really well and is easy to take care of in the lab.

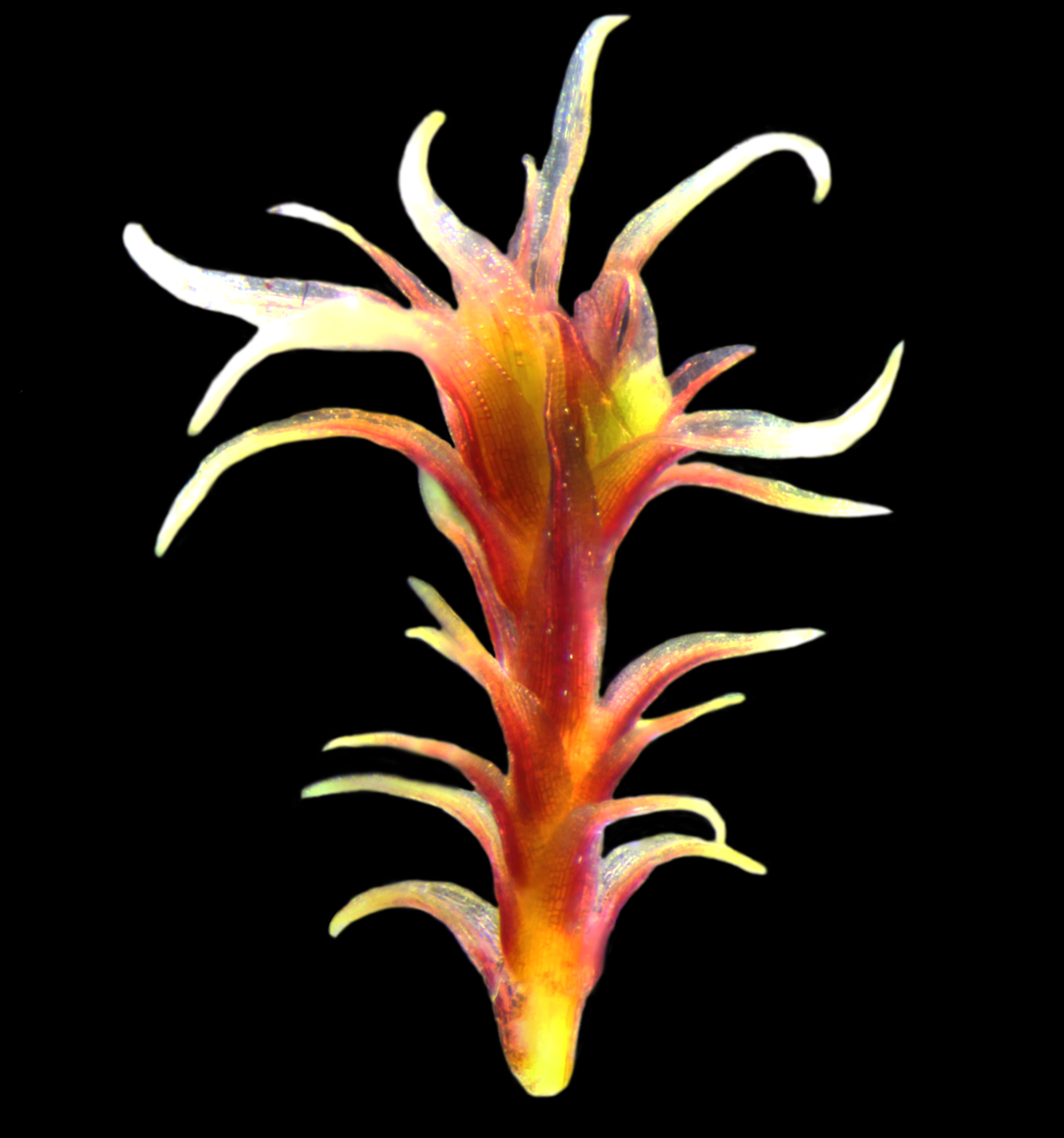

Fire Moss

This is another male Ceratodon purpureus plant. The common name for this species is fire moss. Looking at this image it may surprise you that they are named that for a different reason (see images of sporophytes)! The plant shown is in the gametophyte stage. This means it is haploid where only one set of chromosomes is present. In humans, the haploid stages are egg and sperm. Similarly, male moss gametophytes make sperm and females make eggs. These unite to make a diploid embryo (a.k.a. a baby).

Moss Baby

(image coming soon)

This is a young moss baby (the brown colored tissue) developing on a female gametophyte (green and leafy)! In botanical terms, a moss baby is called a sporophyte. Just like in humans, the baby relies on its mother for nutrients. This moss baby will continue developing and eventually be about 30 millimeters long.

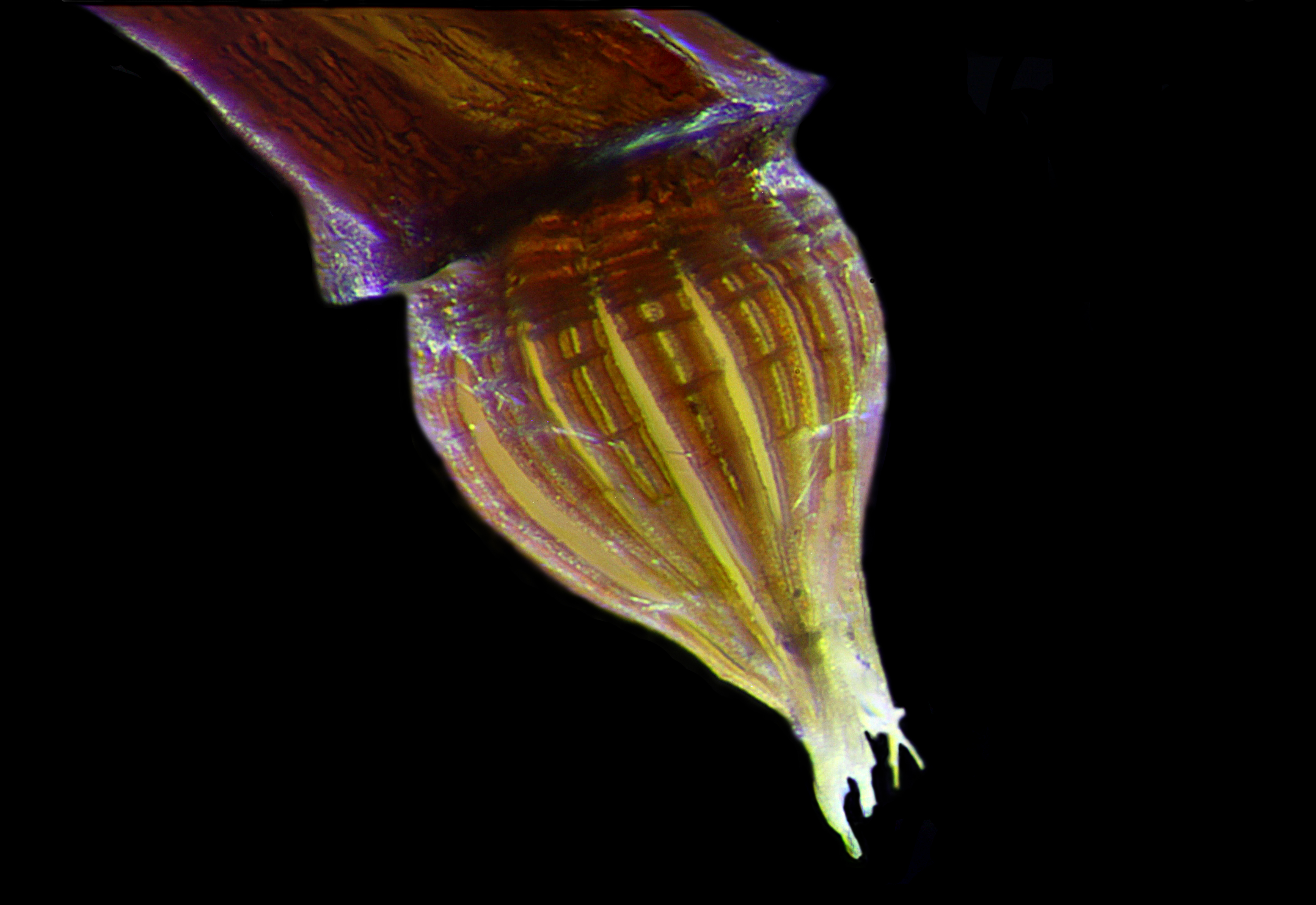

Sporophyte Closed

This is a close-up of a developed moss sporophyte capsule (that is, a fully-grown moss baby). You can see a little of the stalk that attaches the capsule to its mother. Unlike humans, the moss baby relies on its mother for nutrients for its entire life. The red color of Ceratodon purpureus’ sporophytes is where they get their common name of fire moss! This sporophyte has an operculum on (basically a lid) keeping the contents inside.

Sporophyte Open

In this picture, the operculum has come off and another structure called peristome teeth are revealed. Moss sporophytes make spores, which is what the capsule contains, and the peristome teeth help slowly release them rather than all at once. The spores are then distributed by the wind. After they land the spores will eventually develop into the green and leafy gametophytes you see growing on rocks and the side of trees!

Sporophyte Teeth

This is a close-up of the peristome teeth. As you can see there are a lot of intricate details on the peristome teeth! The spores dispersed through these are very small (about 14 micrometers). In the lab, we have to count the number of spores produced in a sporophyte. This is an important trait because each spore equates to more nutrients the mother gametophyte needed to provide. Once all the spores are released the sporophyte will fall off its mother and she can provide for another baby sporophyte.

Moss Placenta

This is a 14 micron thick slice through the region where the moss sporophyte is attached to its mother gametophyte. The mother gametophyte provides nutrients to its baby sporophyte through a placenta, making it functionally similar to the human placenta. In my research I study the genes being expressed in this region to look for signs of conflict between mom’s genes in the gametophyte and dad’s genes in the baby for providing nutrients to the baby.

Several of the pieces from “Art of Biology” 2015 now permanently reside in the UF Biology Department’s conference rooms